Tokenism: The Cooked Spinach of Community Engagement

By: Meghan McCarroll

“The idea of citizen participation is a little like eating spinach: no one is against it in principle because it is good for you.” (Arnstein 1969, p. 216)

Photo from 2jdominic at eatthismuch.com

Arnstein’s analogy from her 1969 seminal work on citizen participation brings to mind a vibrant visual of a steaming bowl of spinach. You can almost smell that iron-rich, earthy stench. It’s a vegetable with numerous health benefits, and yet just thinking about causes disgust for so many people. And it’s this reaction that makes Arnstein’s comparison of spinach to citizen participation so poignant. Collectively, we all like the idea of citizen participation, and yet for one reason or another, we often still find it distasteful and difficult to swallow.

My last job was within a local government, and I continue to work side-by-side with local governments through my dissertation and current research interests. It’s exciting to bring local government to the table, because it means you have a better chance of creating meaningful change. And yet, I often find myself thinking about Arnstein’s spinach analogy. Her theory of the climb to true citizen participation is over 50 years old, and yet it’s still one of the most commonly cited models of community engagement to this day (see Monno & Khakee, 2012; Cai et al, 2015; Bradford, 2016). Which to me implies that we haven’t improved much over the past 5 decades at creating true community engagement and generating real citizen power.

An example for you: I recently assisted a local government with a photovoice project that was developed to incorporate community voice and perspective within a neighborhood planning initiative. The local government essentially wanted to know what the community currently valued, and what they thought needed more investment. They asked a select few community members to take photos that represented their thoughts on these matters.

Examples of participant photos from the final photo book (Artists from left to right: Jo Ann, Victoria Brunner and Liliana Diaz Solodukhin).

It was a monumental opportunity for us as researchers. We had the local government come to us to set this project up. They initiated the community engagement, on an issue that had real power over place, space, and community identity, and they intended to remain involved for the entirety of the project. It was a community-engaged scholar’s dream!

And yet, there were several hiccups as the project rolled out. Why was the recruitment period so short and rushed? Why weren’t there city representatives at all of the photovoice workshops? Why did the final photo exhibit feel flimsy and like an after-thought? And why wasn’t there some way to continue the conversation with other community members beyond the span of the photovoice project? Just when we had solved the last issue, another one seemed to pop up and take its place. In the back of my mind, a small doubt about the purpose of the photovoice project began to emerge. I didn’t know how to express it until I described it to a friend of mine, who named what I was feeling.

“That sounds a little like tokenism”, he said.

If you google the term, the first definition that pops up is from the Oxford Dictionary – “the practice of making a perfunctory or symbolic effort to do a particular thing… in order to give the appearance of equality”. It’s creating an appearance of “doing what’s right” because you have to, or because people are watching, but not really because you want to. It emerges from a variety of sources, particularly through dominant rhetoric surrounding community engagement that views these processes more symbolically than as valuable contribution, or worse, as a waste of time altogether (Monno & Khakee, 2012).

“Tokenism”. It had a familiar scent… A little bit like spinach.

I had actually heard this rhetoric before, without knowing it had a name. It was present at my previous job working in a local government. Coworkers would justify a lack of effort with “I don’t have time for this” or “the public doesn’t really care anyway”.

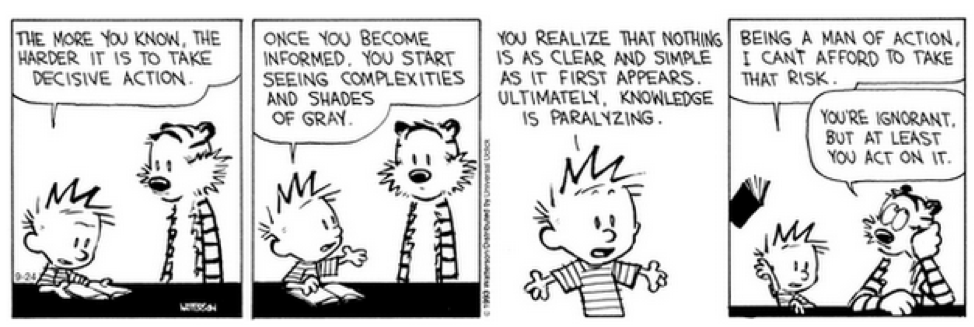

Calvin & Hobbes proving that the public doesn’t *really* want to be involved… (Watterson, 1996)

“Tokenism”. I rolled the term around in my head for a few more days.

And eventually, I came to some important realizations. The first being, that I sort of understand.

You see, I have been the stressed-out, overworked government employee on an understaffed team that was tackling jobs well outside of the original job description, all while navigating the scrutiny of the public eye. I understand all too well that there are always time constraints and low budgets, and not enough hands on deck anyway. Things go wrong, deadlines create limitations, and people are almost always too busy. Sometimes you have to meet people where they are and work together towards the final goal.

I also realized that community engagement – true community engagement – takes a lot of practice.

Every time you try, you learn more about the process. What works and what doesn’t. What specific needs does this specific community bring to the table. And entities like local governments often don’t have a strong history of community engagement. Creating change isn’t instantaneous. It takes time and effort, trial and error. Sometimes it’s about the effort and continual improvement.

Finally, I realized the importance of authenticity – both in action and in appearance.

Overall, my experience with this local government, during this photovoice project, was professional and enthusiastic, and as committed as they could be. Most of the time, I genuinely felt that everyone we were working with was interested in the outcomes, not just for the value of checking a box, but because they wanted to hear from the community and wanted to open the floor to discussions.

That doesn’t mean that there wasn’t a touch of tokenism at play here. The project definitely could have done with a bit more time, a bit less rush, a bit more physical presence and a bit more expression from the city. From my perspective as an insider, I knew the city was authentic. But from an outsider’s perspective, it may not have been so obvious.

But the value of a project like this lies in its ability to voice community opinions. If the community doesn’t see this opportunity themselves, then what’s the point? Authenticity needs to be front and center throughout the entire process. It should be made as clear and obvious as possible. As often as possible. Because it’s better to sound like a broken record than to sound fake.

In the end, I do believe the photovoice project as a whole made an real impact on the neighborhood planning initiative. Voices were heard. It wasn’t perfect, but the effort towards community engagement is still something to be applauded because it’s forward movement. It’s something with momentum that can be continued.

Arnstein (1969) stated that tokenism could actually lead to true citizen empowerment, as long as it creates a two-way flow of information and feedback, and assurance that the people’s concerns and ideas will be accounted for. It’s a step in the right direction.

So yes, sometimes community engagement smells like spinach. But if you just try it, you might find out that it actually doesn’t taste all that bad – and the next time you cook it, you may figure out how to make it even better.

I would like to thank all of the photovoice participants and city employees, who dedicated a significant amount of time, energy, and enthusiasm to make this project possible and help inform the future development of our city!

Meghan McCarroll is a second-year PhD student in geography, researching water literacy levels of urban populations in drought-prone regions. Her prior work has focused on community education and outreach within water management both locally in Colorado, as well as abroad in Australia, and now South Africa. She believes that by involving local communities within water management practices, relationships are strengthened, water projects are improved, and power is shifted to include local community members as decision-makers. She is now working with CCESL as a 2019-2020 Community-Engaged Fellow in Urban Sustainability, focusing on engaging local Denver communities with photovoice research. In her free time, you can find Meghan in the mountains hiking, biking, skiing and snowboarding. To contact her or learn more, visit her portfolio page.