A Democratic Approach to Enhanced Community Listening

By: Kristopher Tetzlaff, ACE Student Scholars Grant Recipient, Morgridge College of Education

Acknowledgements

This community-based research project was conducted under the supervision of Dr. Nicholas Cutforth, lead faculty member in the Research Methods and Statistics Program in the Morgridge College of Education at the University of Denver. I am interminably grateful to the You be You Early Learning community for their participation and indispensable contributions to this groundbreaking educational endeavor. Finally, on behalf of the You be You Early Learning community, I would like to thank DU Grand Challenges and the Center for Community Engagement to advance Scholarship and Learning for funding, in part, this transformational community-based research project.

Principal Academic Researcher

Kristopher Tetzlaff (he/him) is a third-year Ph.D. student in Curriculum and Instruction. He currently serves as an adjunct instructor for both the Office of Internationalization and Languages, Literatures & Cultures at the University of Denver. Kristopher is a cofounder and advisory board member for You be You Early Learning.

Research Question

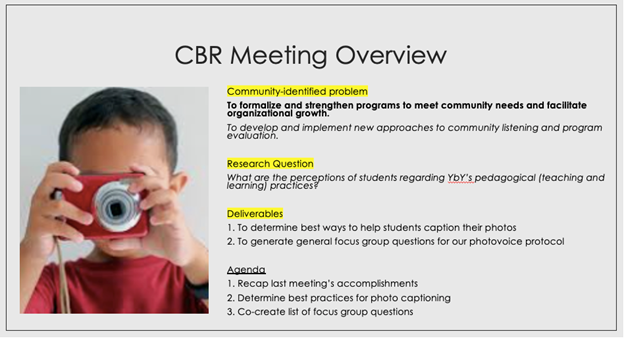

What are the perceptions of students vis-à-vis the humanizing pedagogical practices implemented at You be You Early Learning?

Purpose

Co-researchers will work collaboratively (1) to develop and implement new approaches to community listening and program evaluation; and (2) to co-create an evidence-based photovoice protocol to employ as a data collection tool.

Project Outcomes

Co-researchers identified the three following outcomes of this community-based research project: (1) to enable young children to record and reflect their learning community’s strengths and concerns; (2) to promote critical dialogue and knowledge about personal and community issues through discussion on the images captured; and (3) to raise awareness on a community-specific topic that leads to social change.

Description of Community Partner

You be You Early Learning (YbY) is Colorado’s first and only nonprofit mobile preschool and teacher-led cooperative. Its mission is to promote educational equity by eliminating cost, transportation, and access barriers for families in need. Its intended purpose is to transform social landscapes educational outcomes for every child. YbY proposes two quarterly STEAM Science Discovery sessions for early learners, ages three to five years old. YbY staff embrace holistic, humanizing, and culturally responsive approaches to teaching and learning and engage young children in project-based learning experiences and creative, play-based discovery. Staff currently serve multicultural cohorts of young children and families in two communities–Willow Park and Peoria Crossing–in partnership with the Aurora Housing Authority.

Origin of Research Project

In August 2022, YbY staff and volunteers engaged in a weekend of strategic planning in collaboration with a paid consultant, resulting in a five-year plan for organizational sustainability and thrivance. Principally, YbY seeks to formalize and strengthen programs to meet community needs and facilitate growth. Hence, the community-identified need is to develop and implement new approaches to community listening and program evaluation. Happily, YbY staff and board members expressed curiosity and enthusiasm in embarking on a community-based research approach to address this pressing issue. Although all of the stakeholders involved in this project are novice community-based researchers, many concomitantly serve as gatekeepers who possess indispensable and invaluable community knowledge.

Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

Freire (1970) qualifies humanizing pedagogy as a revolutionary, dialogic approach to teaching and learning that “ceases to be an instrument by which teachers can manipulate students, but rather expresses the consciousness of the students themselves” (p. 51). Humanization, Freire posits, is the process of becoming more fully human as social, historical, thinking, communicating, transformative, creative persons who participate in and with the world. It is the ontological vocation of human beings and, as such, is the practice of freedom in which the oppressed are liberated through consciousness of their subjugated positions and a desire for self-determination (Freire, 1970; Salazar, 2013).

A humanizing pedagogy, therefore, “is that which examines the political and sociohistorical aspects of education and builds upon the sociocultural realities of students’ lived experiences, while centering students as active, critically engaged participants in the co-construction of knowledge” (Salazar, 2013, p. 138). Ultimately, humanizing practices are key to facilitating transformation and the authentic liberation of historically minoritized peoples (Salazar, 2013). Commensurate with Freire’s conceptualization of humanization, Salazar (2021) developed the humanizing pedagogy practices framework (see Appendices), which serves as a practicable means of effectively engaging every stakeholder in the pursuit of mutual humanization.

Until now, the extant body of literature vis-à-vis humanizing pedagogy for early childhood contexts is limited almost exclusively to K-12 and higher educational contexts. It stands to reason that–although all humanizing practices are culturally responsive–not all culturally responsive practices foster mutual humanization and lend themselves to collective, critical, and emancipatory action. To circumnavigate this barrier, I conducted a systematic literature review to determine what culturally responsive instructional practices for young children intersect with a humanizing pedagogy. Therefrom, I developed a novel early-childhood-oriented framework (see Appendices) to inform and guide the co-creation of the YbY photovoice protocol as a data collection tool.

Community-based Research Approach

Commensurate with the Freirean conceptualization of mutual humanization, community-based research (CBR) is “a partnership of students, faculty, and community members who engage in research with the purpose of solving a pressing community problem or affecting social change” (Strand et al., 2003, p. 3). In the context of CBR, the term community comprises groups of folks who share a common interest centered around issues of culture, heath, economic, and/or socio-political import. Additionally, community is inclusive of educational institutions, community-based organizations, and agencies who offer services and/or work on behalf of area residents (Strand et al., 2003). Strand et al. (2003) affirm the three following principles of CBR. First, “CBR is a collaborative enterprise between academic researchers and community members” (p. 8). To elucidate, unique to CBR is the intentional engagement of community stakeholders in identifying a research problem to collaboratively investigate, as well as in the critical action that is generated from the researchers’ findings. Moreover, the collaborative nature of CBR is significant, as it casts the researcher and community stakeholders in a reciprocal, interconnected, and critical role as investigators, teachers, partners, and learners. Second, “CBR validates multiple sources of knowledge and promotes the use of multiple methods of discovery and dissemination of the knowledge produced” (p. 8). Thus, when conducted with integrity, CBR can serve as a culturally sustaining and revitalizing approach to investigation, as it values, considers, and privileges diverse epistemologies and ontological perspectives. Furthermore, CBR operationalized vital community cultural wealth and funds of knowledge throughout the investigative process. Finally, “CBR has as its goal social action and social change for the purpose of achieving social justice” (p. 8). Therefore, community-based researchers must abandon any notion of saviorism and instead work to examine and eliminate their implicit biases while engaging in ongoing critical reflection. This signifies that all parties are beneficiaries of CBR and may therefore leverage the data and findings to ignite meaningful, emancipatory action aimed at transforming social, educational, political, and economical landscapes and outcomes for community stakeholders.

Photovoice as a Data Collection Tool

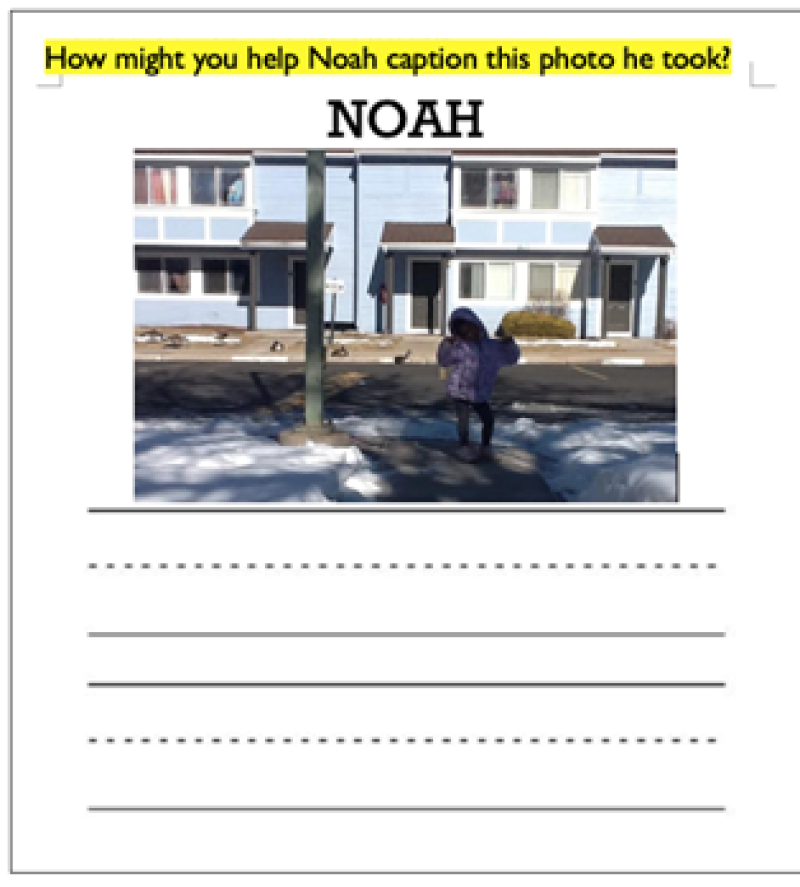

Photovoice is a community-based participatory research method used to document, illustrate, express and share a topic of concern through imagery. It is a creative process of empowerment in which people–often those who are under-represented, marginalized, nonverbal, or with limited power in society–can share their lived experiences through photography. Providing explanations or captions for the photos they produce helps participants to explain their world to others. Through sharing imagery and narratives with various stakeholders, photovoice can raise awareness about a specific issue, leveraged to bring about change (Eckhoff, 2019).

At around 36 months of age, children coordinate the fine movements of the fingers, wrists, and hands to skillfully manipulate a wide range of objects and materials in intricate ways. Children often use one hand to stabilize an object while manipulating it (California Department of Education, 2022).

Thus, the photography element of the photovoice experience is accessible to all students at You be You Early Learning. Giving young children camera devices as data collection tool positions them as co-researchers, renders the research more concrete, provides a different avenue of communication, and affords participants the opportunity to exercise choice over what is important to document (Eckhoff, 2019).

Description of Co-principal Investigators

Happily, I was able to assemble a talented, multicultural cohort of YbY staff and volunteers to serve as community-based researchers for this important endeavor. My research collective comprises one academic researcher and seven co-principal investigators, all of whom were instrumental in co-creating the photovoice protocol. In September 2022, YbY staff and volunteers were approached with the prospect of participating in this pilot case study as community researchers. Six of the staff expressed unwavering interest. Subsequent to viewing our work, yet another YbY advisory board member joined our community-based research team in February 2023. Table 1 below articulates the interests and assets of each co-principal investigator integrally involved in this community-based research project.

Procedure

As the principal academic researcher, I approached this project by examining peer-reviewed research pertinent to conducting community-based participatory research with young children using the photovoice method. Second, I organized and facilitated biweekly community-based research meetings–both virtual and in-person–with the goal of orientating and engaging my co-principal investigators in all aspects of this community-based research project. Table 2 below elucidates the outcomes of each team meeting.

Table 2

YbY Community-based research meeting outcomes

|

Date |

Outcomes |

|

Jan. 6, 2023 |

|

|

Jan. 20, 2023 |

|

|

Feb. 3, 2023 |

|

|

Feb. 16, 2023 |

|

|

Mar. 3, 2023 |

|

In addition to the abovementioned meetings with my research cohort, I met with my faculty advisor, Dr. Nicholas Cutforth, on a biweekly basis to discuss and critically reflect upon my progress vis-à-vis CBR-oriented processes and products relative to this project. Indispensable to the research process, I engaged in analytical memoing subsequent to biweekly meetings to record and detail my impressions, plans, discoveries, and wonderings throughout the CBR journey. Finally, thanks to generous funding provided by DU Grand Challenges and the Center for Community Engagement to advance Scholarship and Learning, I was able to incentivize each of my co-principal investigators for their invaluable contributions to this research endeavor with a gift certificate of their choice.

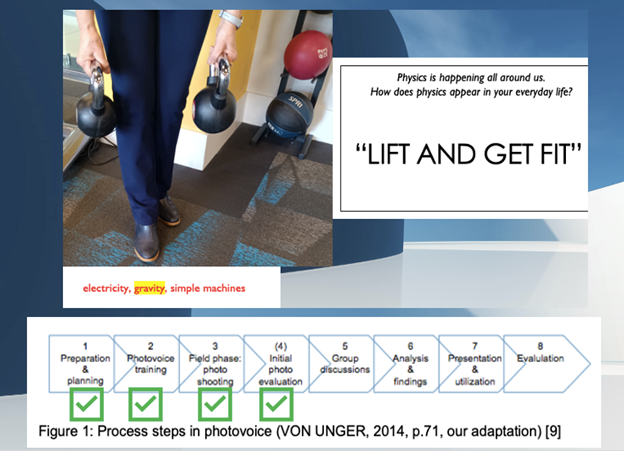

Project Results

In collaboration with my research team, I designed an evidence-based photovoice protocol that comprises six phases. Therein, I articulate the research question, purpose, photovoice method description, project outcomes, aligned standards and social justice elements, and commensurate humanizing pedagogy conceptual framework (Salazar, 2021). Phase I of the protocol elucidates the materials and resources teachers will need for all six project phases; the preparation procedures; and the project duration and timeline.

Phase II articulates how teachers will scaffold photovoice as a formative assessment tool. It comprises requisite materials and resources needed, the purpose of implementing photography-oriented learning experiences, a lesson plan template, a SIOP Model Lesson Planning Checklist, and a menu of scaffolding experiences in which teachers can engage students to acquaint them with photographic devices (i.e. iPads). Additionally, shared folders and resources are hyperlinked therein to facilitate access for teachers and community researchers.

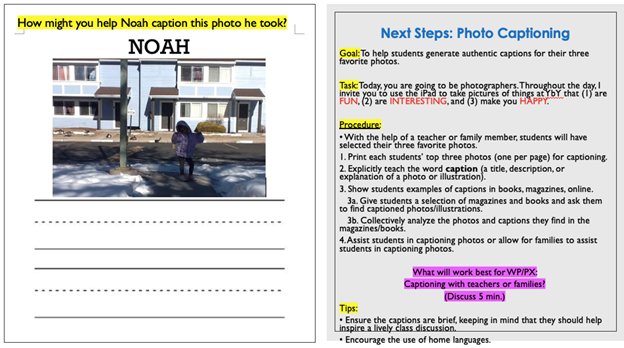

Phase III of the protocol conveys how teachers will engage students in the photovoice experience. It includes the objective, outcomes, and materials and resources required for the third phase of the project. Moreover, it provides teachers with a procedural script to contextualize the photovoice experience and instructs teachers how to ethically acquire assent from their students. Moreover, the protocol outlines procedures for photo device distribution; ways to remind students of the photovoice task; and how to engage students and families in photo captioning.

Phase IV of the protocol informs co-researchers on the detailed steps in co-creating the photovoice products (i.e. digital and hardcopy photobooks). Herein, teachers will find the product description and purpose; required materials and resources; and the detailed procedure and specifications for producing both the digital and hardcopy versions of the photobook.

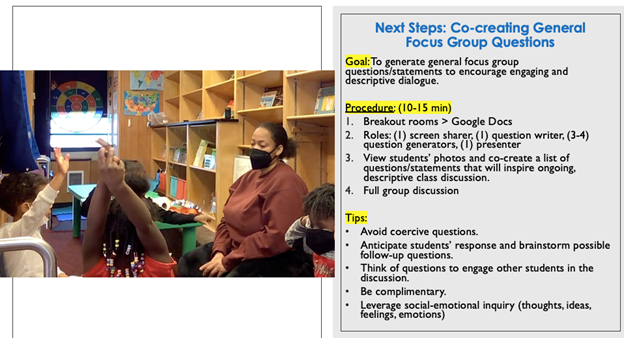

Phase V of the photovoice protocol details how teachers will engage students in the focus group discussion utilizing the abovementioned products as an access point to facilitate descriptive dialogue and deepen data collection. Furthermore, it articulates a focus group script and question bank to elicit and record students’ rich narratives vis-à-vis their selected captioned photos.

The sixth and final phase of the photovoice protocol communicates the procedures for data cleaning, coding, and subsequent analysis. Video tutorials are hyperlinked herein to explain to co-principal investigators how to generate, clean, and code transcriptions using familiar electronic platforms such as Zoom. Lastly, it is punctuated by references, and relevant artifacts (i.e. planning resources, consent forms, frameworks, etc.) are made accessible in the appendices of the protocol.

Scholarly Development

Until now, my most notable lesson gleaned from designing the photovoice protocol as a data collection tool in collaboration with talented team of community researchers is that community-based research is seldom a linear process. To maximize the impact of this project necessitated the sharing and democratization of power, knowledge, and resources with co-researchers. Furthermore, it required that I remain cognizant of and model authenticity, vulnerability, compassion, and critical reflexivity throughout the collaborative research process. In addition, I was compelled to yield to the community’s timeline in order to actively and equitably involve YbY stakeholders in each step of the iterative process.

Second, I discovered that community-based research is an approach that is enlivened via reciprocal teaching and learning. To illustrate, one of my duties was to train YbY stakeholders to leverage their diverse skill sets and to become competent, effective, and ethical researchers. In exchange, I was granted access to a wealth of indispensable community knowledge to enhance the photovoice protocol and products. None of this would have been possible were it not for concerted efforts to build and maintain relational trust and solidarity with community stakeholders.

Finally, I learned evidence-based strategies to effectively and ethically engage students, families, and teachers in the photovoice experience. Involving multicultural young children in community-based participatory research is no simple feat. It requires patience, incessant community engagement, compassion, flexibility, and an elevated degree of intercultural competence. Lastly, because student, family, and teacher demographics vary drastically at both YbY sites, I elected to embed agency, differentiated instructional strategies, and a trove of relevant supplemental resources to ensure teachers at both YbY locations would be satisfactorily equipped to pilot the photovoice protocol next academic quarter.

Applied Learning

Subsequent to Winter Quarter 2023, YbY staff will aim to pilot the photovoice protocol in the Willow Park community. Findings from the photovoice experience will be leveraged to tailor the focus group protocol to deepen and enrich data collection. Thereafter, my co-researchers and I will clean, code, and analyze the data gleaned from the photobook and focus group discussions. YbY staff will then leverage the findings to identify and address pedagogical and programmatic gaps to enhance the overall educative experience of YbY students and families. Furthermore, researchers will extract the pedagogical assets reported by students to include in grant applications, grant reports, and promotional realia. Next, I will seek IRB approval of the photovoice protocol in June 2023 for inclusion in my dissertation research proposal. Finally, I will operationalize the photovoice protocol in Autumn 2023 to collect data vis-à-vis student perceptions regarding the humanizing pedagogical practices implemented at YbY. Ultimately, the data and findings will be integrated in my dissertation research.

Communication with Community Partner

As previously mentioned, this work was communicated to all YbY stakeholders via biweekly community-based research meetings. The protocol, relevant peer-reviewed research, supplemental resources, consent forms, and much more were shared with all co-principal researchers via shared folders in Google Drive. Finally, this project has been consistently conveyed in exceptional detail and with total transparency to the YbY community via various board and cooperative committee meetings, emails, text messages, and newsletters.

Screenshots from biweekly community-based research meetings with YbY co-researchers.